@rvosa is Naturalis no longer hosting Treebase? https://t.co/MBRgcxaBmR

— Hilmar Lapp (@hlapp) May 10, 2022

So it looks like TreeBASE is in trouble, it's legacy Java code a victim of security issues. Perhaps this is a chance to rethink TreeBASE, assuming that a repository of published phylogenies is still considered a worthwhile thing to have (and I think that question is open).

Here's what I think could be done.

- The data (individual studies with trees and data) are packaged into whatever format is easiest (NEXUS, XML, JSON) and uploaded to a repository such as Zenodo for long term storage. They get DOIs for citability. This becomes the default storage for TreeBASE.

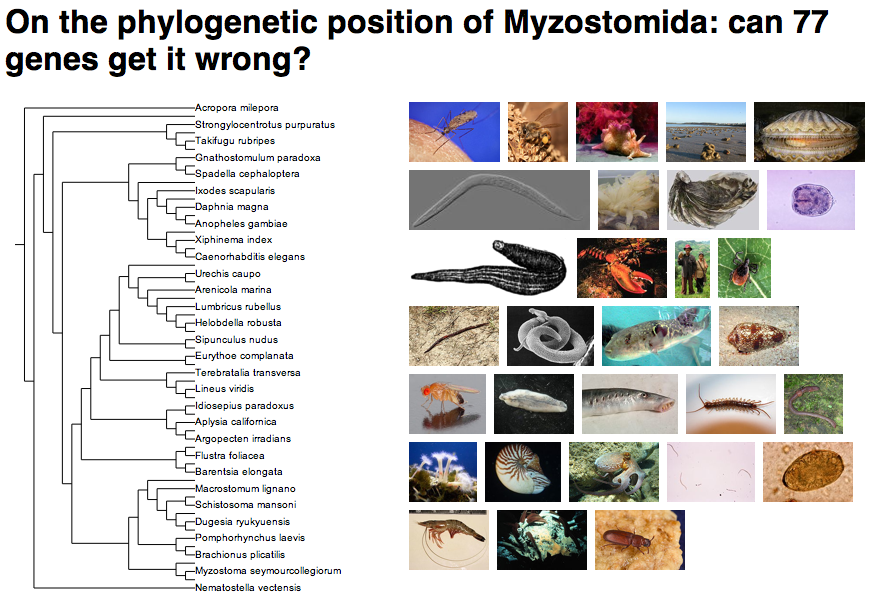

- The data is transformed into JSON and indexed using Elasticsearch. A simple web interface is placed on top so that people can easily find trees (never a strong point of the original TreeBASE). Trees are displayed natively on the web using SVG. The number one goal is for people to be able to find trees, view them, and download them.

- To add data to TreeBASE the easiest way would be for people to upload them direct to Zenodo and tag them "treebase". A bot then grabs a feed of these datasets and adds them to the search engine in (1) above. As time allows, add an interface where people upload data directly, it gets curated, then deposited in Zenodo. This presupposes that there are people available to do curation. Maybe have "stars" for the level of curation so that users know whether anyone has checked the data.

There's lots of details to tweak, for example how many of the existing URLs for studies are preserved (some URL mapping), and what about the API? And I'm unclear about the relationship with Dryad.

My sense is that the TreeBASE code is very much of its time (10-15 years ago), a monolithic block of code with SQL, Java, etc. If one was starting from scratch today I don't think this would be the obvious solution. Things have trended towards being simpler, with lots of building blocks now available in the cloud. Need a search engine? Just spin up a container in the cloud and you have one. More and more functionality can be devolved elsewhere.

Another other issue is how to support TreeBASE. It has essentially been a volunteer effort to date, with little or no funding. One reason I think having Zenodo as a storage engine is that it takes care of long term sustainability of the data.

I realise that this is all wild arm waving, but maybe now is the time to reinvent TreeBASE?

Updates

It's been a while since I've paid a lot of attention to phylogenetic databases, and it shows. There is a file-based storage system for phylogenies phylesystem (see "Phylesystem: a git-based data store for community-curated phylogenetic estimates" https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv276) that is sort of what I had in mind, although long term persistence is based on GitHub rather than a repository such as Zenodo. Phylesystem uses a truly horrible-looking JSON transformation of NeXML (NeXML itself is ugly), and TreeBASE also supports NeXML, so some form of NeXML or a JSON transformation seems the obvious storage format. It will probably need some cleaning and simplification if it is to be indexed easily. Looking back over the long history of TreeBASE and phylogenetic databases I'm struck by how much complexity has been introduced over time. I think the tech has gotten in the way sometimes (which might just be another way of saying that I'm not smart enough to make sense of it all.

So we could imagine a search engine that covers both TreeBASE and Open Tree of Life studies.

Basic metadata-based searches would be straightforward, and we could have a user interface that highlights the trees (I think TreeBASE's biggest search rival is a Google image search). The harder problem is searching by tree structure, for which there is an interesting literature without any decent implementations that I'm aware of (as I said, I've been out of this field a while).

So my instinct is we could go a long way with simply indexing JSON (CouchDB or Elasticsearch), then need to think a bit more cleverly about higher taxon and tree based searching. I've always thought that one killer query would be not so much "show me all the trees for my taxon" but "show me a synthesis of the trees for my taxon". Imagine a supertree of recent studies that we could use as a summary of our current knowledge, or a visualisation that summarises where there are conflicts among the trees.

Relevant code and sites

- CDAO Tools, see "CDAO-Store: Ontology-driven Data Integration for Phylogenetic Analysis" https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-98

- PhyloCommons

Quick thoughts on the recent announcement by

Quick thoughts on the recent announcement by