On first glance Glitch looks weirdly retro, and it took a little while for me to get the hang of things. Bit it's fun and very powerful. Basically it's a place where you can start creating web apps in your browser, and each app is automatically hosted online. If you see an app that you like you can see the source code (just like you can see HTML using "view source" in your browser). if you want to hack on the code you can simply create a copy and it's yours to play with (this is called "remixing", like forking on GitHub). Your copy gets a cute name (possibly annoyingly cute) and away you go.

If you're a developer, then at this point you're probably wondering what is actually happening under the hood. Each Glitch app is a node.js app, which means you're programming in Javascript (you can just use HTML and client side Javascript if you want to avoid node.js). I'm very new to node.js, so Glitch has been a fun way to experiment.

There are two things which make Glitch very powerful. The first is the "remix" feature. Don't know where to start? Find an app that looks like it might do something you want to do, remix it, and hack away. The code is edited online, and the editor works very well. It also checks your code for Javascript errors as you type, which is helpful (usually).

The second great feature is that you get built in hosting for free. As soon as you remix an app you have a functioning web site. Remixing is very like forking in GitHub, and if you're running node.js on your local machine then the benefits of Glitch might not seem obvious. But hosting is often a pain, either you need to set up your own servers, or use a hosting service. Glitch takes care of this for you, so your app is instantly available for others to use.

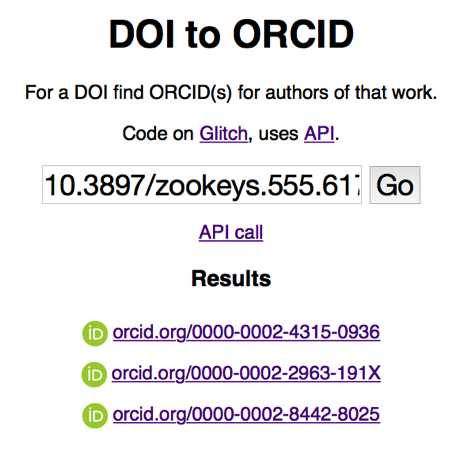

So, what can you do with Glitch? There's some great examples on the Glitch site, but I want to show an almost trivial example. I've created an app called "enchanting-bongo" https://enchanting-bongo.glitch.me (yes, the name is a bit irritating) that does one simple thing. You give it a DOI for an article and enchanting-bongo tells you whether any of the authors of that work have an ORCID. For example, try the DOI 10.3897/zookeys.555.6173. Why did I write this? I'm interested in ways to link people to the work that they've done, especially work that ends up being aggregated in large-scale biodiversity databases like GBIF (see Possible project: #itaxonomist, combining taxonomic names, DOIs, and ORCID to measure taxonomic impact).

The app does one thing. It takes the DOI and calls the ORCID API to see if anyone has claimed authorship of the paper with that DOI. You can use the app with a web browser, or you can use an HTTP client and call the API (e.g., https://enchanting-bongo.glitch.me/search?q=10.3897%2Fzookeys.555.6173).

Glitch is an example of servers computing, where you don't have to worry about physical servers or the software infrastructure that runs on them (e.g., the web server itself), you just write code. Like any buzzword, there is some pushback, see for example What Is “Serverless”? An Alternative Take, but for a fascinating essay I recommend Why the fuss about serverless?. But the notion that I can simply hack away on some code and have an instantly available web app is very attractive.

The other buzzword is "microservices". I'm forever needing to do tasks such as find a DOI for a paper, match a "microcitation" to the enclosing article, locate a specimen in GBIF based on catalogue number in a paper, parse some text into structured data, such as a reference, geographic coordinates, etc. These are tools that I need in lots of contexts, and I've written software to do this on my machine, often as part of larger projects. "Microservices" is the idea that instead of large, monolithic apps we write a series of minimal tools that typically do one thing, and do it well. We then chain the together to do various tasks. Having small tools means that we can treat each problem independently, and if the tools communicate over the web (HTTP) then it doesn't matter what programming language we use. I've started thinking more and more about adopting this model and developing a bunch of small services to perform many of the tasks I need. Hosting these services then becomes in issue, I have web servers in my office but they are a pain to maintain (my university is forever insisting that I upgrade their software), so cloud-based hosting seems the obvious way forward. Free-hosting looks ideal, so Glitch is looking very attractive.

So, I'm hoping to experiment more with this approach. One thing I might do is create a series of services very like enchanting-bongo, have a simple web interface and an API that the web interface calls. That way users can play with it in their web browser, then call the service via the API if it does something useful. As a more sophisticated example of a service, I'm working on tools to parse Wikispecies reference strings, and link specimen codes to records in GBIF.

One reason I'm enthusiastic about Glitch is that it is fun!. Some of the best shifts in technology that I've made have been because a tool made something easy and fun to do. For example, CouchDB made working with structured data fun, and that was a revelation (databases, fun, surely not). Fun is a much neglected characteristic of the tools we use.

Last week I was at

Last week I was at